“No pursuit is ever safe,” Zimmel said. “Every pursuit is dangerous, and nobody ever wants to be in one. I don’t want to crash. I don’t want anybody else to crash.”

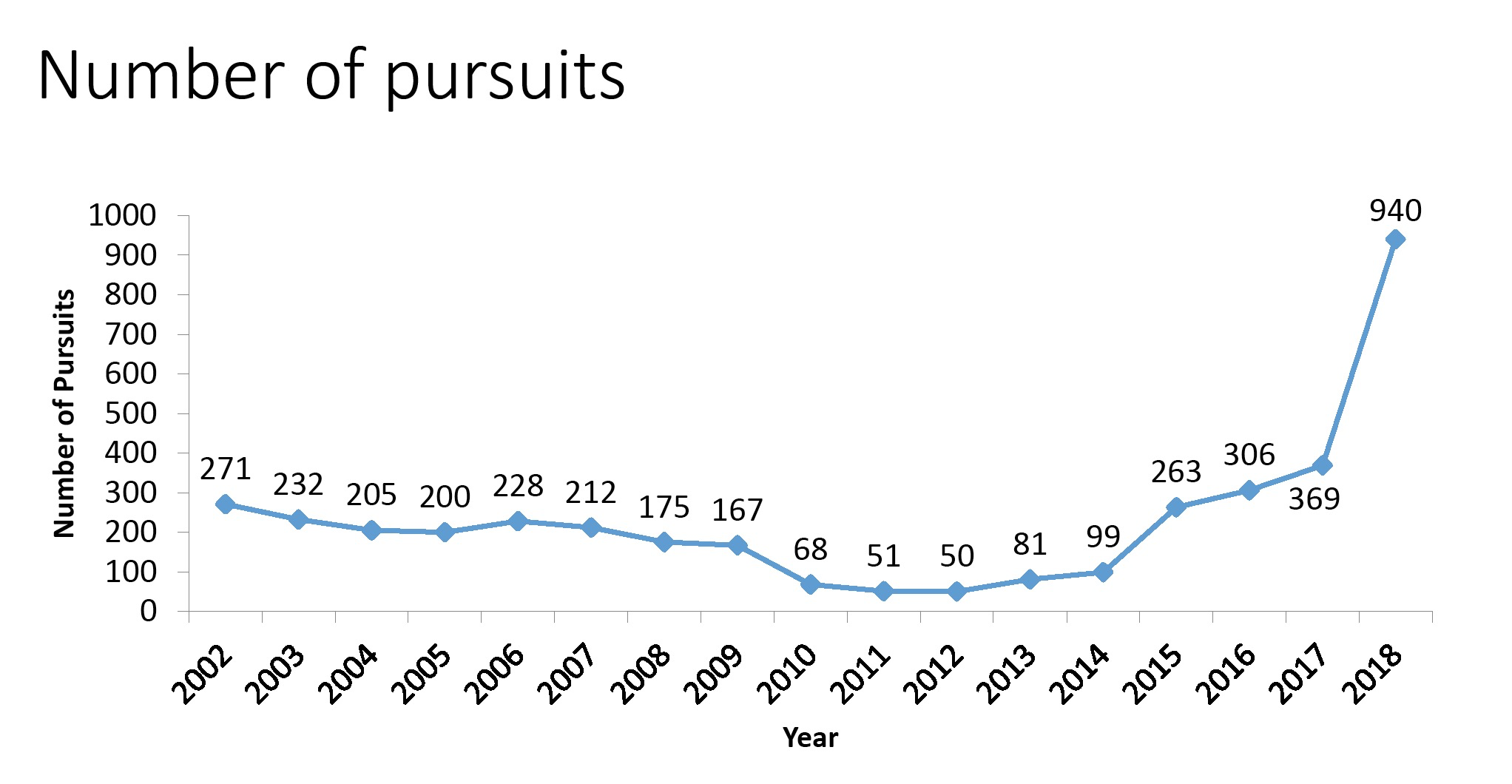

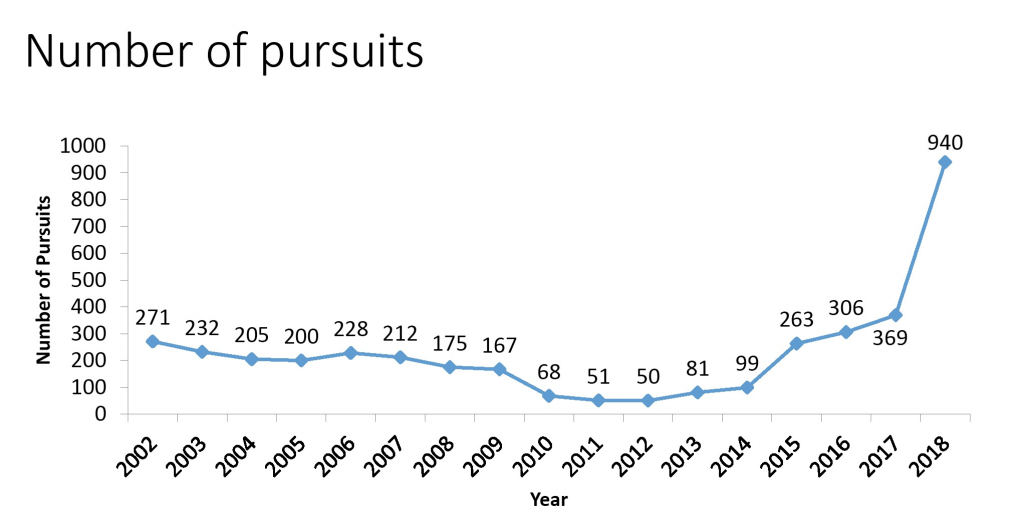

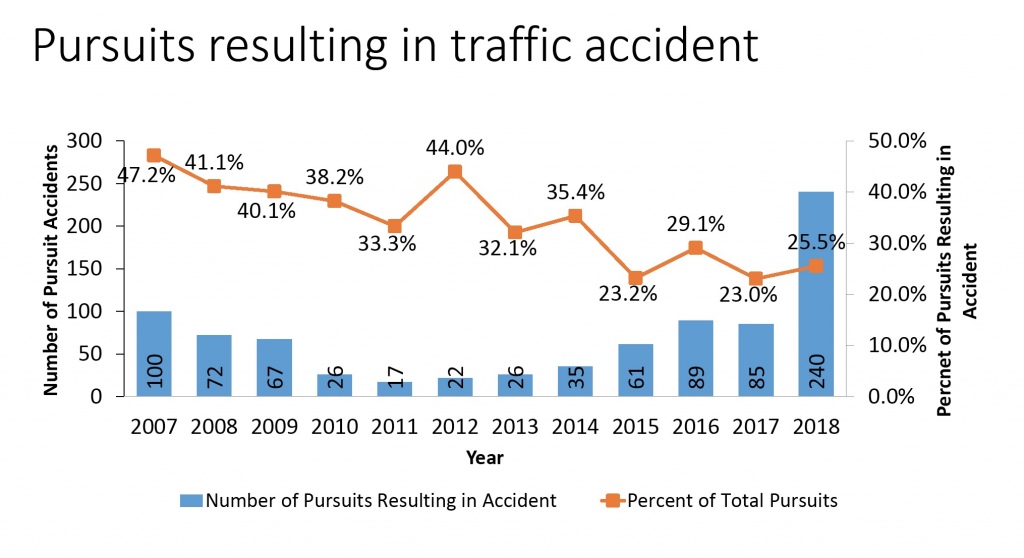

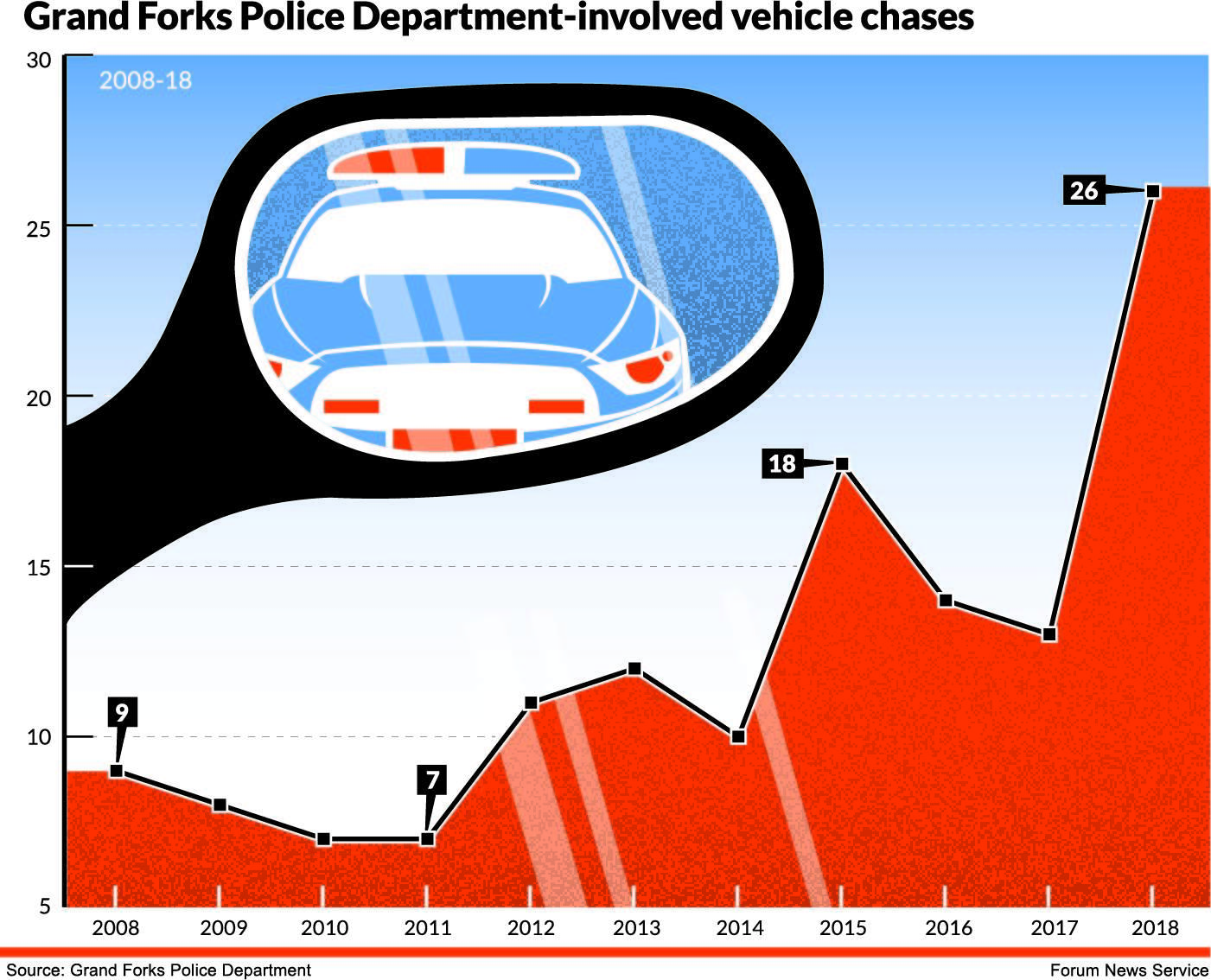

In Grand Forks, 2018 produced 25 police chases for the Grand Forks Police Department, more than any other year in the last decade, according to numbers from the department. The figure was double the 2017 count of 13, and almost three times the 2008 total of nine, according to a Herald analysis. The 2018 number actually reached 26 when counting an unresolved case involving a person on a bicycle.

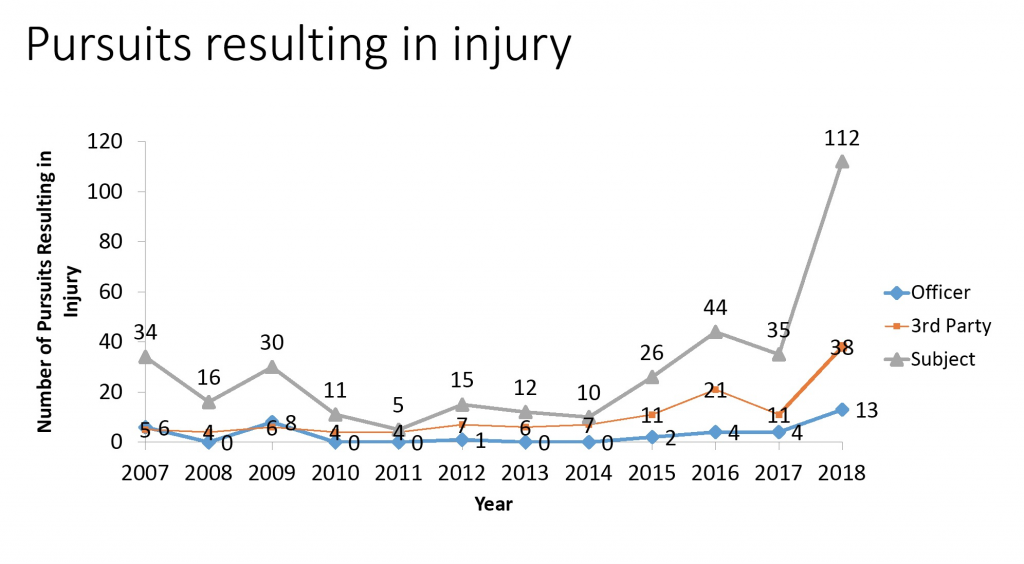

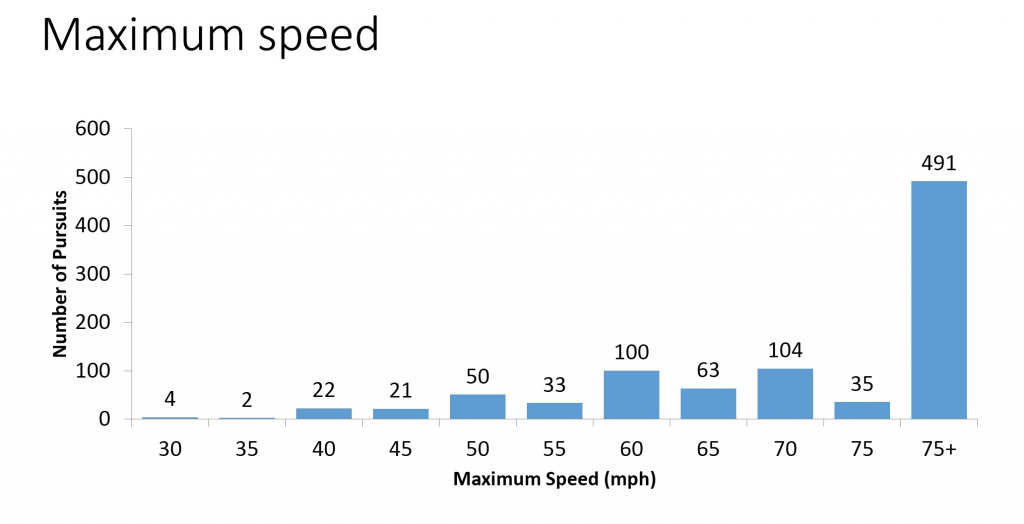

The Herald searched records related to every chase that occurred last year in Grand Forks and found at least 10 exceeded 70 mph within city limits, with five reaching or exceeding 100 mph. Six vehicles crashed, resulting in several injuries and one death.

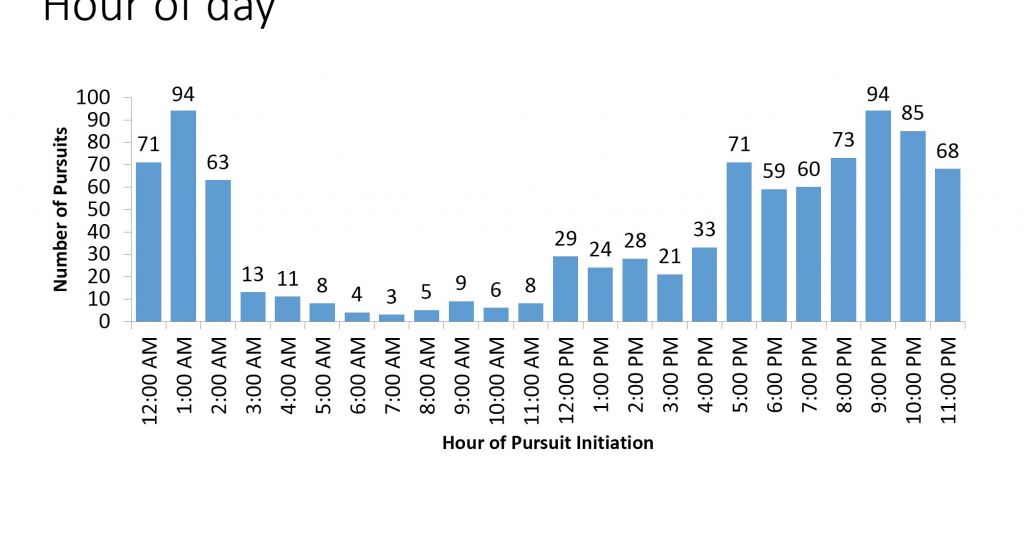

Seventeen of the 25 chases occurred between midnight and 5:16 a.m. Six occurred in a busy span over the final seven weeks of the year.

In several cases, passengers were endangered, including in the December pursuit of Saha Bahaour Darji. According to a police statement, Darji fled on icy roads with two children in the vehicle. In a March pursuit of Michael John Sebjornson, police records indicate a passenger in Sebjornson’s car begged him to stop.

Two patrol cars—one in Grand Forks and the other in East Grand Forks—were damaged by suspects, according to the reports. One person involved in a chase died of injuries sustained in a crash that occurred moments after police called off the pursuit.

Tony James Smith, 33, of Grand Forks crashed his vehicle into a tree near downtown. According to an incident report, Smith fled from officers at approximately 5 a.m. Aug. 2 after a patrol car tried to stop him for expired license plates. Speeds reached 90 mph, and Smith was driving between 59 and 69 mph when he crashed, according to estimates in the report. He died at the scene.

Smith’s death was the first time in a decade that someone died in Grand Forks after an attempted traffic stop. Two people were killed in 2010 after a suspect fled from UND Police and crashed his vehicle into another car.

Other deaths have occurred in the region. A Cavalier, N.D., woman died last year in Pembina County after fleeing deputies and state troopers. A Fargo man succumbed to injuries in 2016 after fleeing state troopers in Cass County.

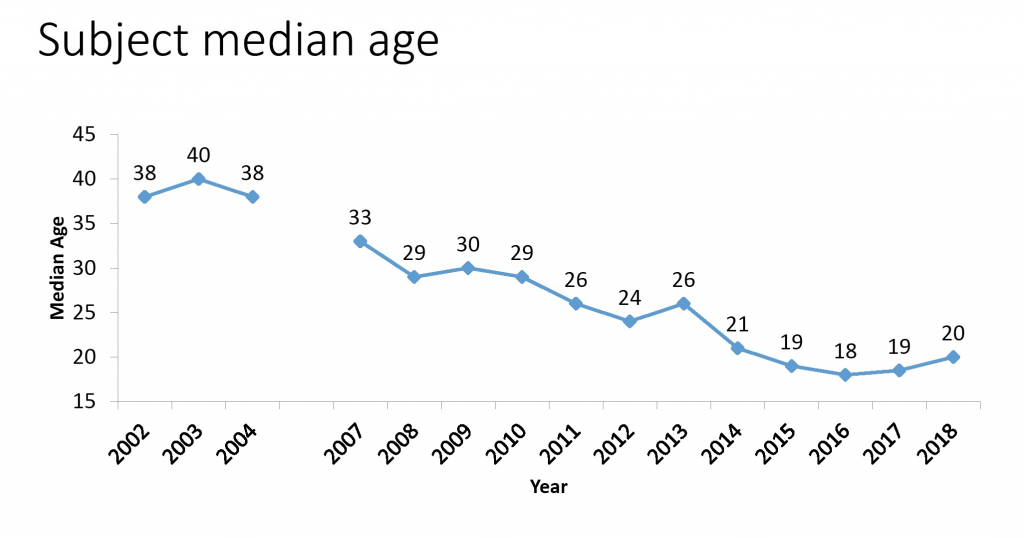

It’s hard to account for the increase in chases or know why suspects flee, Zimmel said. Police may never know why Smith fled, though officers said they could smell alcohol on his breath when they were performing CPR, and they discovered what appeared to be marijuana on his person, according to the police report.

“Why do people run?” Zimmel asked. “It can be personal, that particular person just doesn’t like police. It could be they have something in the car or on their person that they don’t want us to be in contact with.

“It could be anything. It could be just because they think they can get away with it.”

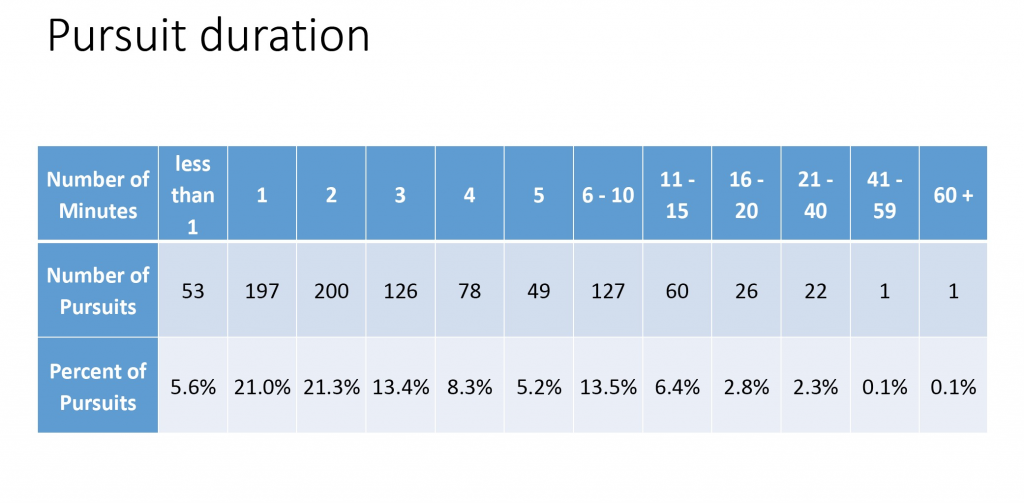

By the numbers

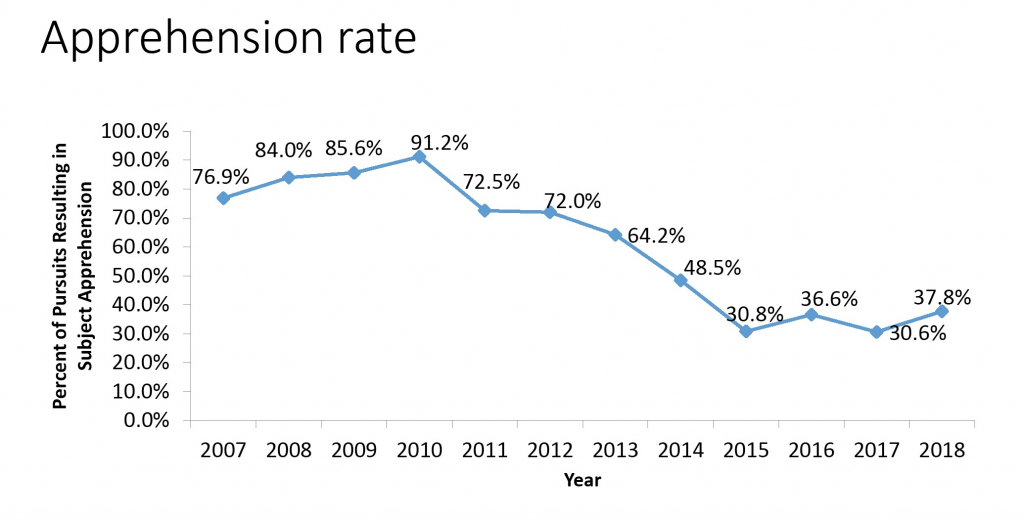

An official breakdown of 2018’s Grand Forks pursuit numbers likely won’t be finalized until at least the end of February, but the Herald’s analysis showed six vehicles stopped voluntarily, eight crashed or got stuck, two suspects fled on foot after exiting the vehicle and five were either cornered by police, stopped after specialized police maneuvers or were incapacitated with spiked strips. Three drivers escaped and were never found.

Two reports were redacted since the chases involved juveniles or the cases are still active. North Dakota law excludes the names of children and summaries from active cases from open record, preventing the information from being released.

The numbers are not official like those found in assessment reports from the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA). Of the 85 chases the Police Department reported in Grand Forks from 2011 through 2017, 14 resulted in crashes and nine people were injured, including one officer and one third-party person, both in 2012.

The increase in total pursuits is not unique to Grand Forks. Across the Red River, the East Grand Forks Police Department recorded eight pursuits in 2018 as of Dec. 21, the most it has seen in a decade, according to figures obtained through the agency. That was up from five in 2017, but all other years recorded three or fewer pursuits.

The records may not be complete, East Grand Forks Chief Mike Hedlund said, but the preliminary numbers show pursuits in his city produced five injuries and no deaths since 2009.

The North Dakota Highway Patrol had 65 pursuits last year, down from a 10-year high of 94 in 2017 but up from the decade average of 57, according to numbers provided to the Herald.

Two Highway Patrol-related chases in the past three years ended with fatal crashes. On April 28, the Pembina County Sheriff’s Department tried to stop Dena M. Peterson, 45, of Cavalier, N.D., the evening of April 28 for reckless driving. The high-speed chase ended around 8 p.m. near Cavalier with a rollover crash that resulted in her death, according to a news release from the Highway Patrol.

In 2016, Dennis Dean Herr, 63, of Fargo died after he crashed into a bridge rail.

Zimmel called last year’s count for Grand Forks “a significant outlier, when compared to pursuits occurring over the previous 10 years.”

“There is an undeniable upward trend in the number of pursuits, and we are mindful of that trend in ongoing training efforts,” he said.

Officers involved

According to the Herald’s analysis, no single Grand Forks officer initiated an usually high number of chases in 2018. Officers Adam Solar, Daniel Essig and Andrew Ebertowski each initiated three chase-related stops last year, the most by any officer in 2018.

Essig was involved in the most chases, being listed in six police reports. Officers Christopher Brown, Mark Nichols, Solar and Ebertowski each were involved in five. Involvement, however, can mean many things in a police report, ranging from supervisors monitoring the situation from afar, officers joining the chase later or others coming to the scene to assist once the pursuit is over.

Sometimes, public property is damaged.

For example, officers in Grand Forks tried to stop Brent Joseph LaFontaine, 32, of Rolla, N.D., in March for several traffic violations, but the chase was called off after LaFontaine crossed over into East Grand Forks, according to a police report. He crashed into an East Grand Forks Police Department vehicle shortly after that, ending the pursuit, the report said.

LaFontaine later pleaded guilty to charges related to the pursuit, which exceeded 100 mph. The news release said “a motor vehicle crash occurred,” but the release did not give details on the crash. The release also did not note that a police cruiser was damaged.

When asked why that information was not included in the release, Zimmel said his police department “will not typically speak on another agency’s actions or investigation.”

In another instance, Grand Forks Police did declare a patrol vehicle was hit by another suspect in November. Cory Will Hanson, who fled after he failed to stop at a red light, hit a patrol car before colliding with a resident’s porch and fleeing on foot.

‘Reasonable suspicion’

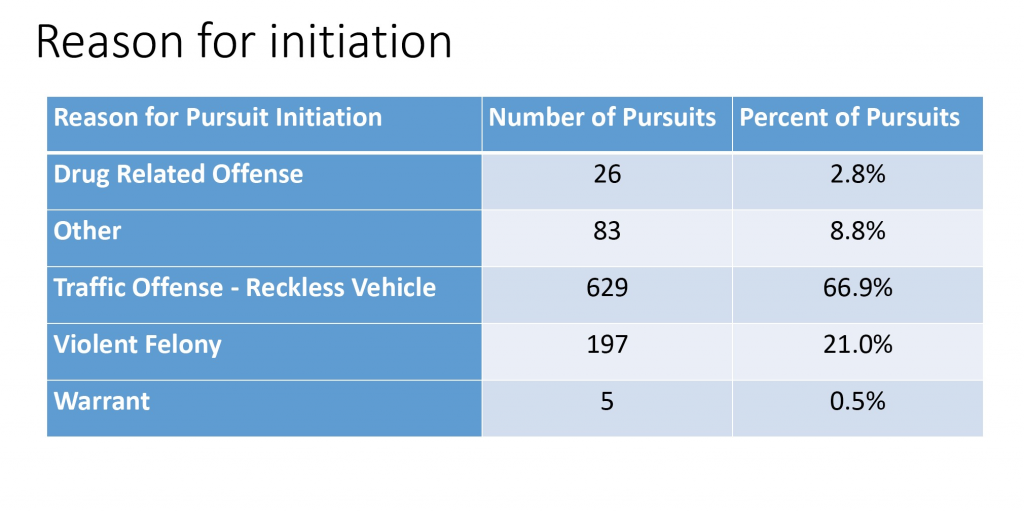

Officers can stop a vehicle if they have reasonable suspicion a person broke the law. The range of reasons for initiating a traffic stop are numerous, from basic traffic violations to suspicion of a stolen vehicle.

“We have to have a reason to flip on the overhead lights,” Zimmel said. “When we flip on the overhead lights, our expectation is that someone is going to pull over to the side of the road in a safe manor and wait for contact with us. Sometimes, they don’t.”

The North Dakota Highway Patrol has had a blend of reasons to initiate stops that resulted in pursuits in recent years, said Sgt. Ryan Panasuk, who has served in the Grand Forks region for 11 years.

“Usually, it is a routine traffic violation or a suspected DUI,” he said.

Last year’s list in Grand Forks produced a number of charges, or possible reasons, suspects fled. Driving under suspension accusations were the most common charges brought against drivers involved in a chase; nearly half of the reports cited that charge. The number excludes resulting chase-related charges of fleeing, reckless driving and reckless endangerment.

DUI arrests also were common in the 2018 count for Grand Forks—seven chase suspects went to court for that reason last year.

Officers have to make a decision whether to pursue a fleeing vehicle based on various factors—weather conditions, seriousness of the violation, familiarity with the area, availability of other officers, etc.

“Officers are placed in a difficult situation,” Zimmel said. “While the stop itself may have been initiated for a simple traffic violation, why is such a violation so threatening to the violator that they are compelled to initiate a pursuit? Is there a likelihood that there is far more going on regarding the incident than was initially known? What is the true threat posed regarding pursuing as opposed to not pursuing?”

Zimmel stresses officers don’t start pursuits. It is the driver’s decision to stop or lead officers on a chase.

“I think that’s an important distinction,” he said. “Law enforcement isn’t the one initiating the pursuit. The violators are the ones initiating the pursuit.”

Fatal ends

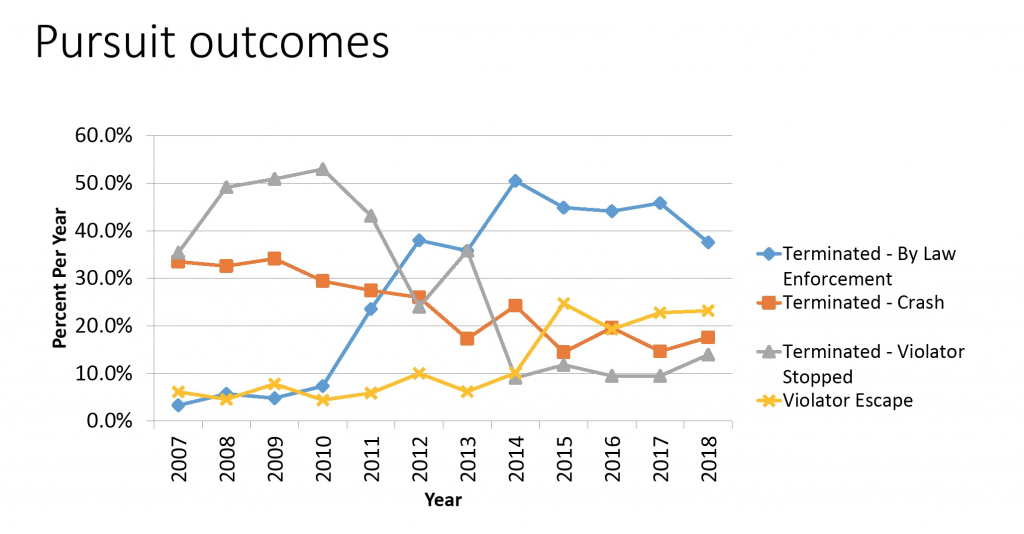

Some circumstances force an officer or supervisor to call off a chase. Deciding whether to terminate a chase is an ongoing process, Zimmel said.

“The conditions can change moment to moment,” he said. “You have to understand that things start moving awful fast, so it’s a very dynamic situation.”

Officers are asked to be mindful of the changing situations as supervisors monitor the pursuits closely in case they need to be called off, Zimmel said. Officers and supervisors can choose to end a chase if the situation becomes too dangerous.

“All personnel are empowered by directive to do so,” he said. “Continuing a pursuit carries a known risk, while discontinuing a pursuit may carry with it an unknown risk. When the known risk outweighs the likely unknown risk, consideration should be given to discontinuing the pursuit, as several were in 2018.”

From 2011 to 2017, the department terminated 19 chases, according the CALEA report. Three chases were terminated last year, and two were canceled due to dangerous conditions, including the chase before Smith’s death, according to the Herald analysis.

In Smith’s case, the chase was terminated due to time of day, lighting, geographical location and danger to the public, according to the police report.

Zimmel is hesitant to say Smith died in a police chase since officers called off the pursuit before he crashed.

“The (death) in 2018 was certainly related to a pursuit, but the pursuit had been terminated prior to the crash,” Zimmel said. “As a result, I’m not sure that incident can be characterized as the driver ‘dying in a police chase.’ ”

That said, Zimmel, who has been with the Grand Forks Police Department for 21 years, said he can’t recall any of his officers being involved in a pursuit in which someone had died.

The Herald could only trace one instance over the last 10 years in Grand Forks when a police chase directly involved a fatality, but that chase was investigated by the UND Police Department. Officers attempted to pull over Celso Garza near Columbia Road and University Avenue after he ran a red light June 5, 2010. He broadsided a car carrying four young adults, two of whom were killed, according to Herald archives. He had been drinking and there was a warrant out for his arrest.

Garza also hit another car during the chase, which reached speeds of nearly 100 mph. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison, according to court documents.

The ones that got away

In 2018, officers also terminated a pursuit in the early morning hours of Nov. 22 at DeMers Avenue and Washington Street due to safety concerns, a police report said. Officers tried to stop the vehicle because of several traffic violations.

At one point, the suspect in the orange convertible Chevrolet Camaro almost hit another vehicle, the report said.

Speeds hit 100 mph before the chase was called off, with officers stating in a police report there were numerous vehicles and pedestrians in the area of the pursuit. Officers never found the suspect who drove the stolen Camaro for about 3 miles, but the vehicle was recovered, the report said.

The third terminated chase was the one that went into East Grand Forks and left the Grand Forks Police Department’s jurisdiction.

Others simply got away. In June, an officer attempted to stop a red car with no rear lights, according to a report. Speeds reached almost 75 mph, and the officer eventually lost track of the vehicle. The suspect was never found.

Suspects don’t always flee in motor vehicles. For example, officers were unable to find a bicyclist who fled Oct. 24 near downtown, one incident report said.

It’s better to terminate a pursuit and let a suspect go when it is too dangerous to proceed, Zimmel said.

“It’s not worth some pedestrian getting struck and killed or rolling a vehicle and a passenger gets injured, a passenger who might have been asking to be let out of the vehicle in the first place,” he said. “Those are far more tragic than if we just let the person go.”

Such was the case for a passenger in the vehicle of Michael John Sebjornson. The 33-year-old from Grand Forks refused to stop for officers during a chase in March, and police used a specialized maneuver to end the pursuit. One of the passengers later said she begged Sebjornson to stop multiple times during the chase. Another passenger had no idea why he was fleeing.

Real life vs. movies

Police pursuits are glorified in television and movies. Zimmel mentioned “The Fast and the Furious,” a multi-movie franchise that features car races and law-enforcement pursuits. He said those scenarios do not reflect what happens in real life.

“There’s a sense that what you see on TV and in the movies is a reflection of real life,” he said. “Huge issues don’t get solved in 45 minutes plus commercial breaks.

“In a pursuit, you’re driving faster than you want to through an area that perhaps you’d rather not be in. You’re having to think about a thousand things at once.”

The latest numbers from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, a government entity created by the Justice Systems Improvement Act of 1979, said police vehicle pursuits resulted in more than 6,000 fatal crashes from 1996 to 2015, adding up to more than 7,000 pursuit-related deaths. A USA Today analysis from 2015 said more than 5,000 bystanders and passengers died in police car chases since 1979.

Chases are stressful because officers don’t know what they are heading into when they attempt to stop a vehicle, Sheriff Chief Deputy Dave Stromberg said.

In January 2017, Rolette County Deputy Colt Allery and other deputies attempted to stop Melvin Gene Delong, 28, of Belcourt, N.D., in a rural area near Rolette. The chase at times exceeded 80 mph, and when the vehicle finally stopped, Delong fatally shot Allery as the deputy approached the vehicle.

Delong also was killed after officers fired at him.

That incident is in the back of many officers’ minds, Stromberg said.

“Pursuits are very much an unknown,” Stromberg said.

Safety played a key factor in making sure the numerous chases in Grand Forks didn’t end with more injuries or fatalities, Zimmel said, adding the department always considers the well-being of not just the people in the vehicles but the residents in the area of the pursuits.

“I think there is definitely a recognition of the potential hazard there,” said Panasuk, the Highway Patrol sergeant. “If someone is trying to stop you, you just stop.”

Two high-speed police chases in Milwaukee since April 11 have left two people dead and at least six others injured.

Two high-speed police chases in Milwaukee since April 11 have left two people dead and at least six others injured.